I’ve talked a lot about Another Star 2’s production and its gameplay mechanics, but so far I haven’t said very much about its story. Since RPGs as a genre are so narrative-driven, I suppose that’s a little strange. Today I’ll finally introduce the game’s setting. Small parts of what I’m going to share here I’ve touched on before elsewhere, but this is the first time I’ve really discussed the game’s story in any detail. Hopefully it sounds like something fun you’ll all want to experience and play through just as much as I want to create and share it.

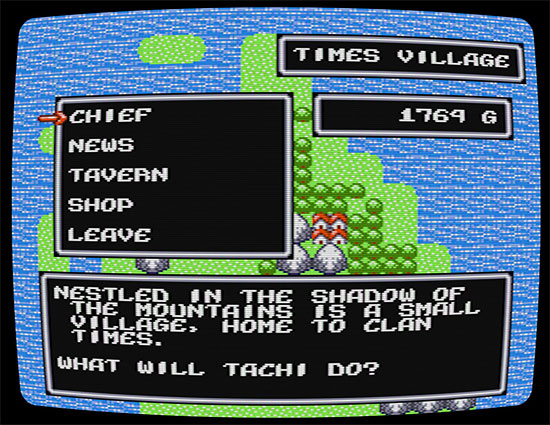

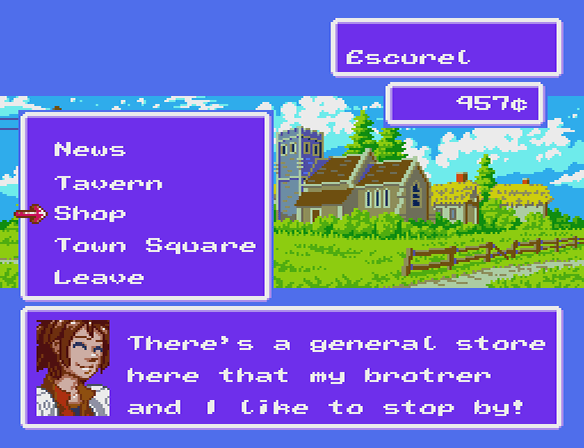

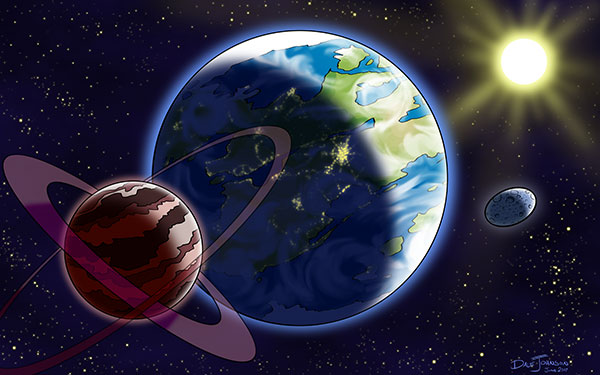

The events of Another Star took place on the planet Mathma, a world full of warring clans that struggled against one another in ever-shifting alliances, eager to increase their own power and glory no matter the cost. The story of Another Star 2, however, takes place on a brand new world called Byo. Byo is a world of magic, swords, and fantasy, but also a world of technology and gunpowder, a planet populated with civilizations at all sorts of levels of development. Numerous species coexist on Byo, though humans are the most populous by far.

Like most habitable planets, Byo is a world teeming with monsters. Those traveling are advised to take the normal precautions, to have their sword or firearm at the ready, and to stick close to the roads if they don’t want to run into too much trouble. But unlike Mathma, Byo is really quite peaceful. There is a stable balance of power between factions and, while armed struggle is not unknown, it has been generation since Byo has seen open warfare.

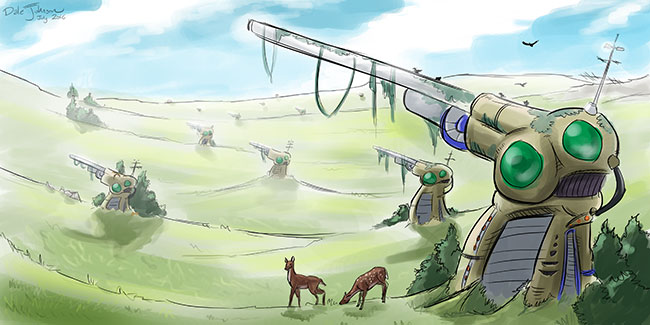

Byo may seem like a very Earth-like planet, but do not be fooled. It is no mere rock. Beneath its thin surface is a planet-sized mechanism of unknown purpose and provenance. Whatever advanced beings created this world are long gone, but a legion of synthetic custodians, widely assumed to be some manner of robots, now look after it deep below the surface. Whether these custodians were also created by the beings that created the planet itself, no one can say for sure. They rarely venture above ground, and even more rarely do they speak. Their only purpose, it seems, is to keep the planet’s core running.

The planet has two moons, Exo and Origin. Exo is the smaller of the two, a mundane oblong sphere that it likely a captured asteroid. Origin is the more exceptional of the two, just as mysterious as Byo itself. Origin is covered in thick clouds and absolutely nothing is known of its surface, if indeed there is one. Probe and manned craft alike dissolve almost instantly upon contact with the moon’s cloud cover. However, it seems that something must be active beneath the clouds. Occasionally, material drifts up from below, gathering in the moon’s rings. This material includes organic compounds, suggesting the possibility of life. The rings periodically eject their contents, leaving bits to tumble down to Byo. What doesn’t burn up in Byo’s atmosphere always seems to land in the same place, piling up in a toxic heap overgrown with enormous fungus. Perhaps Origin’s strange behavior is fundamentally tied to Byo’s operation somehow?

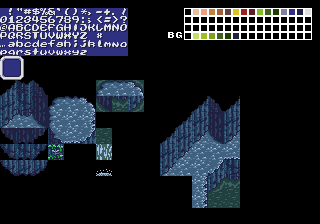

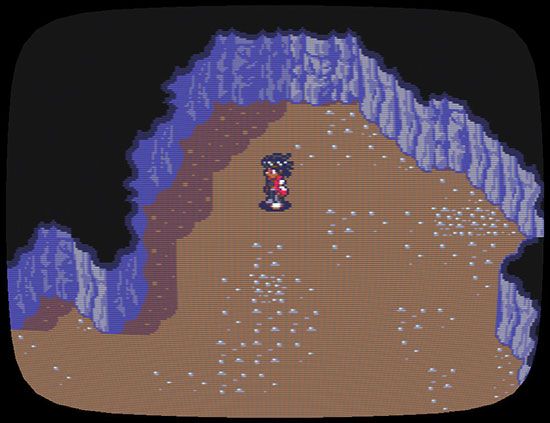

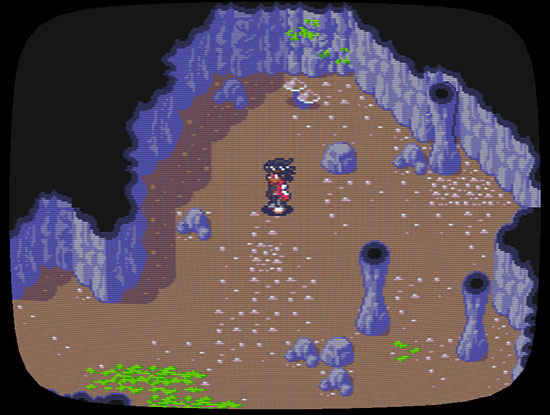

Countless alien structures litter the landscape of Byo, exterior parts of the complex mechanisms below. They are a common sight, though their exact purpose can only be guessed at. What are they for? What do they do? Are they still functional?

For the most part, the people of Byo just don’t really care. All they know is that they’re a free source of electricity. You can easily plug into the planet’s power conduits where they come up to feed these structures, so it’s common for people to build up around these structures. The planet’s robot custodians still tend to these alien structures, maintaining them just enough to keep them from becoming completely overgrown. If they’re bothered by others siphoning off the planet’s power, they’ve yet to say or do anything about.

Byo’s modern history stretches back many thousands of years, with many different space-faring civilizations arriving to find this strange world, colonizing it and tweaking it to suit their needs, but never fully claiming it for their own. Thus it’s no surprise that it contains more recent ruins that clearly do not originate from the planet’s original creators. Sometimes younger, fledgling peoples take up residence in the fallen cities of more advanced civilizations that arrived before them, while other times very advanced civilizations may find a home by modernizing a more primitive ruin.

But Byo’s specific state as a lush planet of blue and green can be traced back to roughly ten thousand years ago. In that time, when few other civilizations had arrived, an extremely powerful human faction known as the Novar landed here and undertook its most extensive terraformation. The planet’s alien shell was covered in oceans, grass, mountains, and forests. They built a great many vast cities, full of skyscrapers built of glass and steel that reached up to the heavens. But, for some unknown reason, they suddenly left Byo, leaving only a tiny fraction of their kind behind. These remnants would become the ancestors of the humans now living on Byo.

The world of Another Star 2 is certainly one of many mysteries. However, these mysteries are about to unravel very quickly, and at a most inopportune time. Despite its long history of peace, in truth Byo is very much a powder keg just waiting for the right spark to set it off. Tensions on the surface of the planet are starting to pile up very quickly. Rifts between factions are starting to widen, and old wounds that never quite healed are in danger of being reopened. Moreover, a power most foul is growing desperate, as a certain event elsewhere in the galaxy has led to unexpected consequences.

In the midst of this looming tragedy about to unfold, a young woman in search of adventure begins to take her first steps into the wide world…